|

| Photo by Mark Rain |

We analyse the relationship between geopolitical and capitalist

dynamics underlying the decision to go to war. Importantly, we argue that only

through a focus on the internal relation

between geopolitical and global capitalist dynamics can we begin to comprehend

the way the Iraq War contributed to the continuation of capitalist accumulation

through what we refer to as a strategy of bomb and build.

Inter-imperialist

rivalry, ultra-imperialism and the transnational state

We start by developing our argument through a critical engagement

with classical and contemporary historical materialist thinkers and their different

conceptualisations of geopolitics, noting three distinct positions. First, drawing

on the earlier work of Lenin and Bukharin, Alex Callinicos

analyses the Iraq war as a case of inter-imperialist rivalry between the U.S.

and its ‘coalition of the willing’, on one hand, and France and Germany, but

also China on the other hand. What his focus on U.S. imperialism, however,

overlooks is the fact that large parts of the internal oil market are highly

integrated and completely outside the control of any one particular state.

Second, Leo

Panitch and Sam Gindin can be noted for their emphasis on co-operation

between capitalist countries under the leadership of the U.S. state in securing

access to oil. Rather than highlighting rivalries between the U.S. and other

states, these authors emphasise the continuity of inter-state co-operation,

whether through collaboration

with intelligence services or airspace deals over rendition and torture

centres. To some extent this position mirrors the classical ultra-imperialism

thesis of Karl

Kautsky and his focus on a ‘holy alliance of the imperialists’ in managing

the global political economy.

|

| Photo by openDemocracy |

Third,

we critically engage with William

Robinson and his transnational state thesis, in which he argues that the transnational

state exists as a loose network of supranational

political and economic institutions combined with national state apparatuses

that have become dominated by transnational capitalist classes. The argument is

that the transnational state used the U.S. state apparatus in order to impose

the interests of a newly dominant transnational capitalist class on the global

economy.

Ultimately, what all three approaches have in common

is their conceptualisation of the external relationship between geopolitics and

global capitalism, or the separation of the political and the economic. These

spheres are held as two

distinct logics, a geopolitical and a capitalist logic, so that the internal

relations between these two dynamics are missed.

The

importance of the philosophy of internal relations

Following on from our International

Studies Quarterly article and in contrast to the above positions, our

main focus is to assert the philosophy

of internal relations as the

hallmark of historical materialism. Developed by Bertell

Ollman, the philosophy of

internal relations implies that the character of capital is considered

as a social relation in such a way that the internal ties between the means of

production, and those who own them, as well as those who work them, as well as

the realisation of value within historically specific conditions, are all understood

as relations internal to each other. Thus, historical materialist analysis is

at its best in understanding the character of capital as a social relation in

such a way that the ties between capitalism and geopolitics are understood as interior

relations.

How does this then help in assessing the agency of state power, or geopolitics, and the structural context of capitalist expansion surrounding the war in Iraq? Transnational capital is not understood as externally related to states, engaged in competition over authority in the global economy. Instead our focus shifts to class struggles over the extent to which the interests of transnational capital have become internalised or not within concrete forms of state and here in particular the U.S. form of state.

How does this then help in assessing the agency of state power, or geopolitics, and the structural context of capitalist expansion surrounding the war in Iraq? Transnational capital is not understood as externally related to states, engaged in competition over authority in the global economy. Instead our focus shifts to class struggles over the extent to which the interests of transnational capital have become internalised or not within concrete forms of state and here in particular the U.S. form of state.

Class struggle in the U.S. form of state and the strategy of bomb and

build in the Iraq War

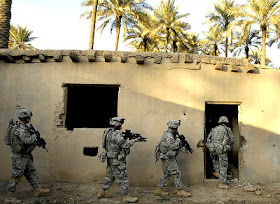

Our

argument is that protecting and promoting U.S. geopolitics through the use of

force has long been a strategy of neo-conservatives who were at the heart of

the George W. Bush administration reflecting the interests of a national

fraction of capital. With multilateralism at an impasse within the United

Nations, the rhetoric of neo-conservative unilateralism gained salience, while

the interests of transnational capital were side-lined within the U.S. form of

state. A dominant discourse of U.S. unilateralism at that time emerged, linked

to the nationalist wing of the U.S. elite rooted within national fractions of capital

tied to the arms industry and key construction companies such as Bechtel. This

wing retained firm roots within the Military-Industrial-Academic-Complex, key

to understanding some of the dynamics of U.S. geopolitics.

|

| Photo by Alice |

Unsurprisingly,

companies part of this national capitalist class fraction were also the ones

receiving the most contracts from the aftermath of the Iraq War. Halliburton

was given a huge contract to run the Green Zone in Baghdad and was hired to

help run the ‘living

support services’ of the Coalitional Provisional Authority. As reported in The New York Times, it was also

given ‘the exclusive United States contract to import fuel into Iraq’ and in

March 2003 ‘was awarded a no-competition contract to repair Iraq’s oil

industry’, having already received more than $1.4 billion in work. The major

U.S. engineering company Bechtel, in turn, was given the first contract awarded

by USAID in April 2003, and was awarded a second contract in January 2004, tasked

with providing ‘a major

program of engineering, procurement, and construction services for a series of

new Iraqi infrastructure projects . . . at a total value of up to $1.8 billion’.

Furthermore,

in terms of the contractual reconstruction of the built environment in Iraq, the role forged in the early days by the U.S.-led

Office of Reconstruction and Humanitarian Assistance in Iraq involved a main

$680 million contract for the reconstruction of electrical, water and sewage

systems, which was granted to the Bechtel Group. The senior vice-president of

Bechtel, Jack Sheehan, was a member of the Defence Policy Board, a Pentagon

advisory group whose members were approved by the Secretary of Defense, Donald

Rumsfeld. George Schultz, the former secretary of state, was also on Bechtel’s

board and chaired the advisory board of the pro-war Committee for the

Liberation of Iraq. The contract was, at the time, the largest of an initial

$1.1 billion reconstruction project headed by the United States Agency for

International Development. It also led to further awards to Bechtel to repair

airports, dredge and restore ports such as Umm Qasr, rebuild hospitals,

schools, government ministries and irrigation systems, and restore transport

links, with the Guardian

reporting that it gave ‘Bechtel an overwhelmingly important role in

virtually every area of Iraqi society.’ A $7 billion contract for controlling

oil fires was also awarded to Kellogg, Brown & Root, a division of

Halliburton, once run by vice-president Dick Cheney.

|

| Photo by Alan Feebery |

Ultimately,

we conclude in the article, that the war on Iraq therefore reflects a

capitalist accumulation strategy of bomb

& build. Our analysis demonstrates the importance of the creation of

the physical infrastructure in the built environment through fixed capital

within conditions of global war as one way of providing temporary relief from

the problems of overaccumulation and the crisis tendencies of capitalism. The

internal relation of geopolitics and global capitalism can therefore be read

through the complex internal linkages of bomb

& build in relation to the Iraq War.

In

other words, through new imperialist interventions in Iraq and, perhaps,

elsewhere (Afghanistan, or Libya), we can witness the spatial reordering of the

built environment through militarism and other mechanisms of finance linked to

specific class fractions within the U.S. state form and thus the policy of bomb and build on a world scale.

This

post was first published on the Progress in Political Economy blog at

Sydney University. Alex Callinicos wrote the reply ‘Fighting The Last War’, to

which Adam D. Morton responded with his post ‘Anti-Bukharin’.

Andreas.Bieler@nottingham.ac.uk

6 July 2015

Prof. Andreas Bieler

Professor of Political Economy

University of Nottingham/UK

Andreas.Bieler@nottingham.ac.uk

Personal website: http://andreasbieler.net

6 July 2015

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments welcome!