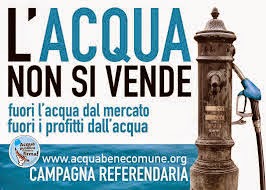

Last week the Italian Water Movements Forum (Forum)

celebrated the anniversary of the victory

in the 2011 referenda against water privatisation by giving great emphasis

to news coming from Chile: the halt by the Chilean government to the Hydro Aysen hydropower project.

The project consists of five big dams to be built along two rivers in the Patagonia

region by an international consortium led by the Italian government owned company

Enel. This emphasis on foreign policy issues does not arise from the fact that

in contemporary Italy there has been nothing to celebrate after and beyond the

2011 referendum. On the contrary “la

lotta continua” and is still very active both at national and local level,

with the struggle for “water as human right and commons” becoming a

paradigmatic battle for democracy and against the commodification of human

life, inspiring also other social mobilisations around the commons. In this

guest post, Emanuele Fantini

discusses the struggles of the Italian water movement with a particular

emphasis on the role played by Catholic groups.

The attention paid to the struggle against big

dams in Chile indicates two characteristics of the Italian water movement. First, its cosmopolitan dimension and the

capacity to act at different scales, holding together global water issues and

local struggles. This peculiarity of the Italian water movement cannot be

easily found within other social mobilisations in contemporary Italy. Second, the

active role that Catholic groups, individuals and organisations, have been

playing within the Italian water movement. In fact the struggle in Chile was

brought to the attention of the Italian water movement and of the broader public

during the 2011 referendum campaign by Luis Infanti de la Mora, Bishop

of Aysen (with Italian origins). These two issues are closely related because

the Catholic groups active within the Italian water movement have been among

those more concerned with the international dimension of the mobilisation.

I have recently analysed the role and

contribution of Catholics within the Italian water movement in the article

“Catholics in the making of the Italian water movement. A moral economy”,

published in the open access journal Partecipazione e

conflitto. The Open Journal of Sociopolitical studies and freely

downloadable here.

In this post, I would like to recall two aspects of this commitment that allows

to highlight two main features of the whole Italian water movement: 1) the multiple

meanings of the notion of “water as a commons”, facilitating a vast social

coalition with heterogeneous political backgrounds within the Italian Water Movements

Forum, as well as expressing a plurality of political grievances and meanings

associated with water; 2) the inclusiveness of the water mobilisation in Italy and

the capacity by the Forum to promote new political allegiances and identities,

rather than simply summing up already existing political actors and groups.

The Forum articulated its struggle against the

privatisation of water services around the notion of “water as a human right

and commons” and translated the issue into an inherent question of democracy,

as affirmed in the Forum’s motto “You write it water, you read it democracy”.

As Chiara Carrozza and I have shown in the book we edited on the Italian water

movement – available here

in open access – the notion of the commons might entail a plurality of

meanings. At least three different approaches to the notion of “water as a commons”

coexist and overlap within the Italian water movement: i) the cosmopolitan

approach of “water as a common good of humankind”, highlighting the global

dimension of water issues and promoting the participation in transnational

networks against water privatisation as well as the implementation of

international solidarity projects; ii) the local approach of “water as a

commons of the territory”, emphasising the local and civic dimension of the

struggle, (re)inventing local identities and (re)discovering the local

territory, advocating for water services governance and management by municipal

actors rather than regional multi-utilities companies, national bodies or

transnational companies; and iii) the radical approach of “water as a commons

beyond the public and the private, beyond the state and the market” that

entails a sharp criticism of representative democracy institutions and explores

new patterns of citizens’ direct political participation in the governance and

management of local services.

All these three different approaches to “water as

a commons” resonate with the Catholic Social Doctrine (CSD) message on water

management and the promotion of the common good. The acknowledgment of water as

a human right and commons has been explicitly included in the CSD, affirming

that “as God’s gift, water is a vital element, essential for survival and

therefore a universal right; water resources and its uses should be oriented to

the satisfaction of everybody’s needs and in particular to the need of people

living in poverty”. Moreover, CSD recalls that “given its nature, water cannot

be treated as a mere commodity among others and its use should be rational and

fair” and that “the right to water, like all human rights, stems from human

dignity and not from a mere quantitative evaluation considering water only as

an economic good. Without water life is endangered. Therefore, the right to

water is universal and indefeasible”. The management of water should be

inspired by the principles of fairness, sustainability, international

cooperation, and poverty alleviation. The different approaches to the commons

by the Italian water movement find relevant correspondence in the principles of

universality, subsidiarity and solidarity that CSD associates with the notion

of common good.

The most exhaustive formulation of these

positions is the one by the Pontifical Council for Justice and peace which last

year published the book “Water.

An essential element for life”. The Pope and the Italian bishops have

reaffirmed these positions in several official statements.

The correspondence between the Italian water

movement frame and CSD facilitated the mobilisation of Catholic groups, particularly

during the referendum. Catholics have been involved since the very beginning in

the Italian water movement at the end of the 1990s. The international roots of

the mobilisation defined the profile of Catholic actors and organisations.

These actors belong to the group – a relative minority within the broader

Catholic constellation - of individuals and associations inspired by Christian

pacifism and internationalism: faith based development NGOs belonging to

FOCSIV-Volontari nel mondo (the Christian Federation of Italian Development

NGOs), alter-globalisation groups encompassing Catholic activists such as Rete

di Lilliput, pacifist associations such as Pax Christi and missionaries like

Alex Zanotelli. Catholic participation in the mobilisation widened during the

2011 referenda. Groups like ACLI (Christian Workers Association) or “Beati i

costruttori di pace” (Christian pacifist group) joined the Referendum Promoting

Committee. Others like AGESCI (Catholic Scouts Association) or the Jesuit

Social Network gave official, external support. Additional support came through

the adhesion of the Conference of the Missionary Institutes and the Dioceses

Network on Sustainability, as well as from several dioceses and parishes.

These groups’ commitment shares several

features with the whole water movement. First the spontaneous and bottom-up

nature: Catholics’ participation in the water mobilisation has not been

promoted and orchestrated by the Church hierarchy, as it was for instance the

case during the 2005 referenda on assisted fertilization. Rather, Catholic

activism has been the result of local groups’ and individual believers’

interests and commitment. Second, Catholics’ presence in the mobilisation has

been mimetic. Catholic identity influenced little the whole movement’s identity

and its repertoires of contention. While significant in terms of individual

biographies of Catholic militants, the participation in the water mobilisation

fell short of reorienting the way dominant Catholic groups conceive their civic

and political commitment. Third, the ecumenical character of the mobilisation

for public water offered the opportunity for many people to get involved in

politics - for the first time or as a renewal of past commitment - on a “noble”

theme, perceived as being above partisan and short-term interests. Thus, for

several Catholic believers and organisations, the water mobilisation offered

the space to combine the affirmation of principles and identities with co-operation

and relationships with actors from different backgrounds.

The spontaneous and mimetic character of the

Catholics’ commitment within the Italian water movement inevitably implies a

certain degree of fragmentation and, therefore, the difficulty to assess the

scope and the specificity of their contribution. For sure, Catholics have been

particularly keen in emphasising the moral, symbolic and cultural aspects of

the contention, consolidating a broad and popular consensus over the principles

of social justice and universality that should inspire water management. The

emphasis on the moral aspects has been considered a key factor in ensuring wide

identification with the water movement and adhesion to the mobilisation,

particularly during the referenda, as shown by social psychologists Davide Mazzoni

and Elvira Cicognani.

Thus rather than awakening traditional religious

and political allegiances, the Italian water movement constitutes an original

experience – also by virtue of the very nature of water – in which a plurality

of political backgrounds cohabit and gave birth to a new political identity -

the “water people” - and patterns of participation - “the commons movement”.

These are relatively new developments within the Italian water movement that

deserve further enquiry.

Emanuele Fantini (emanuele.fantini@gmail.com)

is research fellow at the University of Turin, Department of Cultures, Politics

and Society. His research interests focus on the political sociology of water

management and water movements, the processes of state formation in Africa with

particular focus on Ethiopia, and the role of universities and research within

development cooperation programs. He has been working with the Italian Ministry

of Foreign Affairs, the United Nations and different Italian NGOs in Ethiopia,

Morocco, South-Sudan, Serbia and Italy.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments welcome!