Privatisation is a truly fantastic thing. Privatising public services

would result in four benign consequences, we are told: (1) the production of

services becomes more efficient and, therefore, cheaper; (2) the quality of the

services is improved; (3) the cost of services for the consumer is reduced; and

(4) companies providing these services can still make a profit. And this all as

a result of private services being subject to the competitive pressures of the

free market. Like a perpetuum mobile, a hypothetical machine which continues to function once activated,

privatization would have an inevitable and continuing positive impact once

implemented. In this post, I will critically evaluate these claims

against the background of my research on the Italian water movement against

privatisation (see Road

to Victory and La

lotta continua) and discuss why it is that this discourse continues to

enjoy such widespread acceptance, although it is empirically so obviously

wrong.

Privatising water in Italy – the empirical developments on the ground.

Water privatisation in Italy started in the late 1990s, early 2000s

especially in the region of Tuscany but also some other locations in central

Italy. Suez arrived in Arezzo in 1998 and in Firenze in 2001. In 1999, Veolia

bought a stake in the water company in Aprilia in the region of Lazio. Almost

immediately upon privatisation, prices for consumers increased drastically,

while investment in the maintenance of infrastructure went down. As one of my

interviewees told me, the price for water in Arezzo is now four times as high

as in Milano, where water services are still run by a publicly owned company. Less

investment in infrastructure, in turn, undermines the quality but also

efficiency of managing water provision in the future.

Privatisation in other areas and countries have also taught us that they

generally come hand in hand with downward pressure on wages and working

conditions of these companies’ employees. As a result of the privatisation of

some units of the National Health Service (NHS) in the UK, for example, pension

benefits have been cut and salaries eroded, resulting in a two-tier workforce

in the health system overall, with employees in the privatised part being

employed on inferior conditions to employees in the public part. Of course, it

is only a matter of time until the currently better conditions of the latter

will be assimilated to the conditions in the private sector as a result of

market competition.

In short, these fantastic, mysterious benefits of the perpetuum mobile of privatisation do not

materialise in reality. Why is this?

The objective of capitalism: profit maximisation.

In the capitalist social relations of production, it is not only

workers, which reproduce themselves through the market, but also employers,

capital. They are in constant competition with other capitalists for market

share. Should they be unsuccessful, they will go bankrupt. It is this constant

competitive pressure, which makes capitalism such a dynamic production system,

but also implies that it is prone to periodic crises as a result of

overaccumulation (David Harvey), a situation when no further profitable

investment opportunities can be found for the re-investment of profits from

past business dealings.

Importantly, the purpose of making profits is not to satisfy any

specific needs of capitalists. Despite of all the fancy cars, luxurious yachts

and expensive houses individual capitalists may buy themselves, they will never

be able to use up all the profits in their own private consumption. They are

simply too high and this not only for the 400 richest people in the world.

Instead of private consumption, profits constantly have to be re-invested in

order to generate yet further profits and, thus, stay ahead under the pressures

of capitalist competition. The type of production, in which profits are

invested, does not matter. Money is used to generate yet more money. This is

the current problem. We are in a situation of overaccumulation, in which the

enormous amounts of private wealth in the global economy find it increasingly

difficult to establish new opportunities for profitable investment. And this is

the moment, when the privatisation of public services comes in.

The provision of certain public services such as education and health,

water and energy, is the responsibility of the state in industrialised,

developed countries. The privatisation of the production of these services has

not implied to date that the state would give up on this responsibility. In

fact, states have set up regulatory agencies to oversee the private production

of services, as it occurred in the case of water in Italy, when a regulatory

agency was established to set the tariffs for the whole industry. And it is

this state responsibility, which makes the privatisation of services like water

such an attractive investment opportunity for capital. At times, when the

global economy is in crisis, investing in services provision, with profits

guaranteed by the state and state bailouts ensured should anything go wrong,

promises super profits, when any other investment opportunities have dried up.

It is profit maximisation, which drives privatisation, and not the efficiency

and quality of the services provided. The latter is simply the discourse with

which privatisation is justified.

As the case of water in Italy demonstrates, profits cannot only be

reaped through increasing the price for water or reducing the investment into

infrastructure maintenance. As I was told in interviews with activists from the

water movement, there were clear instances of cartel formation, when two

consortiums were both bidding for the contracts in two different areas and

withdrew shortly before the conclusion of the competitive tender in one area

each, ensuring that both of them secured one contract without the public authorities

having been able to engage in any meaningful negotiations about the contents of

the contract. Moreover, the contracts for infrastructure maintenance, which

privatised water providers do put out, often end up with subsidiaries of these

private providers.

Why do public authorities then carry out privatisations considering that

the assumed benefits are simply not materialising in reality?

The power of capital

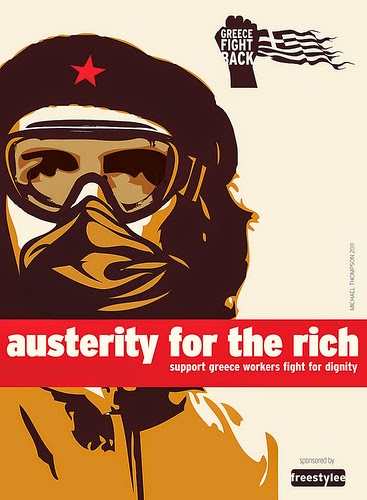

|

| Photo by freestyle |

Nevertheless, it is also the structural power of large TNCs and their

ability to threaten governments with the moving of production facilities or the

withdrawal of investment, should they not pass legislation facilitating TNCs’

operations. Especially in times of economic crisis, when the situation is

already bad, pressure of this type weighs heavily on the minds of

decision-makers.

The possibilities of resistance

And it may be the discourse around the commons, collectively

owned and administered by the people, which may provide a basis for challenging

the discourse of the perpetuum mobile of

privatisation.

Prof. Andreas Bieler

Professor of Political Economy

University of Nottingham/UK

Personal website: http://andreasbieler.net

7 May 2014

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments welcome!